Induction machines operate via electromagnetic induction. A rotating magnetic field from the stator (3-phase AC, 50/60 Hz) induces current in the rotor, creating torque. Slip (2-5%) enables motion without direct electrical connection.

Table of Contents

ToggleElectromagnetic Induction

Assuming the rated power of an electric motor is 200 kW, its efficiency typically ranges from 90% to 94%, which means that for every 1 kWh of electrical energy consumed, approximately 0.9 to 0.94 kWh is converted into mechanical energy. The global motor market grows at an annual rate of around 6.5%.

Some high-efficiency generators can achieve efficiencies of over 98%. For a 500 MW thermal power plant, approximately 4.9 billion kWh of electricity is generated annually, with 2% (about 98 million kWh) being wasted due to low equipment efficiency. By improving the generator’s efficiency, even a 0.5% increase could save up to 24.5 million kWh of electricity annually.

Assuming a transformer has a rated power of 50 kW, a high-efficiency transformer’s annual power loss would be reduced to about 1 kWh, while a traditional transformer could have a power loss of up to 5 kWh annually, representing a 400% difference. Some high-efficiency induction cookers can achieve thermal efficiencies of over 90%, offering a 40% energy-saving advantage compared to traditional gas stoves.

The rotational speed of a robotic arm can reach 5,000 rpm, with an error margin controlled within ±0.01%. Through these automated systems, production efficiency can increase by more than 30%, while labor costs are reduced, saving approximately 20% in production expenses.

A typical electric drill has a power rating between 500 watts and 1,500 watts, and using a high-efficiency motor can improve working efficiency by about 15% and reduce equipment failure rates. The widespread use of smart grids is expected to improve the global power system efficiency by about 7%.

When charging an electric vehicle, the cost of electricity is about 0.4 RMB per kWh, while the fuel cost for a traditional gasoline car to travel 100 kilometers is over 15 RMB. The energy efficiency of electric vehicles is three times that of traditional vehicles. By optimizing electromagnetic induction principles in battery management systems, the efficiency of battery charging and discharging can be improved by about 15%.

Rotating Magnetic Field

If the frequency of the stator’s rotating magnetic field is 50 Hz (i.e., it changes 50 times per second), the rotor’s speed must match the frequency changes of the stator to remain fully synchronized. For a typical 50 Hz induction motor, the synchronous speed is 3,000 rpm.

If the rotor speed is 2,950 rpm, the slip is 50 rpm. For these motors, the slip typically ranges from 0.5% to 6%. As the load increases, the slip increases, meaning the induced current and the driving force become stronger. Assuming a wind turbine generates 3 MW (3,000 kW) of power with a motor efficiency of 95%, the actual energy input required would be 3,157 kW.

If a more efficient motor is used, improving efficiency to 98%, the input power required for the same 3 MW output would decrease to 3,061 kW, saving 96 kW of energy consumption. The magnetic field coupling efficiency between the stator and rotor can exceed 98%, and in some special high-efficiency motors, this efficiency can approach 99%.

For a motor with a rated power of 100 kW, the energy loss per hour is typically between 1 kWh and 3 kWh. Some transformers can achieve an efficiency of 99.2%, meaning that for every 100 kW of input power, less than 1 kW of energy is lost during the conversion process.

Assuming a large city’s electricity demand is 1,000 MW, if the loss per kWh is reduced by 0.1%, nearly 8.76 million kWh of electricity can be saved annually, which is equivalent to reducing energy costs by about $430,000. When the motor’s frequency changes from 50 Hz to 60 Hz, the speed increases from 3,000 rpm to 3,600 rpm, allowing it to meet varying load demands.

Electric vehicle motors typically use a rotating magnetic field for propulsion, achieving efficiencies of over 90%. Assuming the battery capacity of a Model 3 is 75 kWh, after a full charge, the vehicle’s maximum range is 500 kilometers, yielding an efficiency of 6.67 kilometers per kWh.

An electric toothbrush with a power rating of 100 watts operates at 30,000 rpm and uses the vibrations produced by the rotating magnetic field to help clean the teeth. Compared to traditional manual toothbrushes, the cleaning efficiency of electric toothbrushes is over 50% higher.

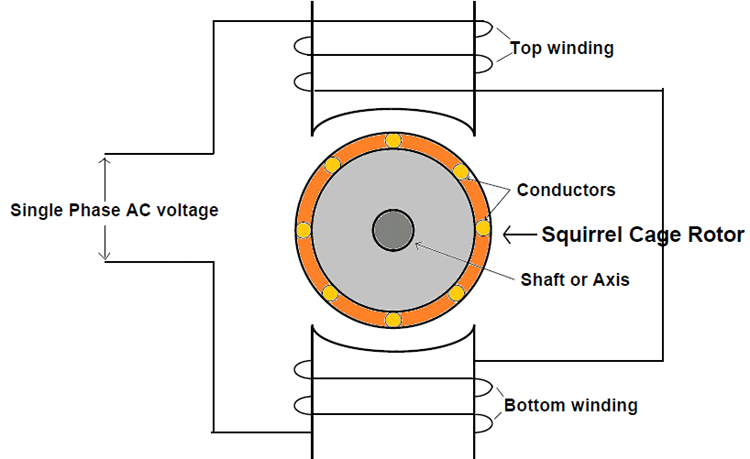

Stator and Rotor

A standard three-phase induction motor with a power rating of 75 kW typically operates with a stator current frequency of 50 Hz or 60 Hz, while the rotor speed varies depending on the load. For an electric motor with a rated power of 150 kW, the current in the stator windings typically ranges from 120 to 150 amps, and with a stator current frequency of 50 Hz, the magnetic field generated by the stator rotates at a speed of 3,000 rpm.

By optimizing the design of the stator windings, the efficiency of the motor can be improved by about 5%-10%. In the case of a 200 kW motor, the rotor usually has 12 to 24 aluminum or copper bars. Under the influence of the stator’s rotating magnetic field, the rotor induces current, generating rotational motion.

The slip of the motor typically ranges from 0.5% to 6%, which directly affects the motor’s power output. For a 100 kW motor with a slip of 3%, the actual power output of the motor would be 97% of the rated power, or approximately 97 kW.

Properly designed stator and rotor magnetic field distributions can improve the motor’s power factor by 5%-10%. In a 500 kW motor, the temperature rise of both the stator and rotor is typically kept within 75°C.

For a 300 kW motor, using high-quality silicon steel sheets and copper rotors can reduce the motor’s total loss to less than 1% of the rated power. A smoothly running motor typically has a vibration amplitude of less than 0.1 mm, while high-quality motors can keep the vibration amplitude below 0.05 mm.

Current Induction

Assuming a 50 Hz three-phase motor, the rotating magnetic field generated by the stator will induce current in the rotor due to the stator’s magnetic field changes. For a motor with a rated power of 75 kW and a rated speed of 1,450 rpm, the corresponding slip is 2%. In this case, the induced current in the rotor is approximately 3%-5% of the stator current.

For a 100 kW motor, the induced current loss in the rotor generally accounts for 5%-7% of the total motor loss. When the stator current frequency increases from 50 Hz to 60 Hz, the induced current in the rotor also changes, which alters the rotor speed. For example, a 100 kW motor will have the rotor speed increase from 3,000 rpm to 3,600 rpm when the frequency is increased from 50 Hz to 60 Hz, resulting in a 10%-15% change in the rotor current.

Using copper-aluminum alloy materials for the rotor reduces the current induction loss by 15%-20% compared to traditional aluminum rotors. For a 500 kW large motor, optimizing the rotor design to reduce current induction loss by 10% can save about 20,000 kWh of electricity annually, equivalent to a savings of approximately $10,000 in electricity costs.

For a 150 kW motor under full load, the rotor current typically accounts for 10% of the stator current, while under light load, the rotor current may only be 3%-5% of the stator current. A 200 kW motor with 10% more turns in the stator windings than the standard design will increase the strength of the stator current by 5%-7%, thereby enhancing the motor’s output power and efficiency.

For every 1 m/s increase in wind speed, the motor speed increases by approximately 2%-3%, effectively boosting output power. For a 400 kW motor, the starting current is five times the normal operating current. Using a star-delta starting method, the starting current can be reduced to twice the rated current.

Energy Conversion

For a motor with a rated power of 200 kW, at rated load, the electrical input to the motor is 200 kW, and the efficiency of converting this electrical energy into mechanical energy is typically between 90% and 95%. This means the actual mechanical output power would be between 180 kW and 190 kW.

For a 500 kW motor with an efficient design, the energy conversion efficiency can exceed 98%. This means that for every hour of 500 kW of electrical input, approximately 490 kW can be converted into mechanical energy. However, if the motor’s efficiency is lower, such as at 90%, only 450 kW of mechanical energy will be produced per hour.

For a 150 kW motor operating at 50% load, the energy conversion efficiency is approximately 95%. However, when the load increases to 100%, the efficiency may slightly decrease to around 93%.

A 1,000 kW large motor, using high-quality materials, can reduce energy waste by about 200,000 kWh annually, resulting in savings of approximately $100,000 in electricity costs. A variable frequency drive motor with a rated power of 300 kW, under light load conditions, can reduce the energy input to 160 kW, achieving an energy conversion efficiency of 98%.

The temperature rise of a motor should not exceed 75°C; beyond this point, the insulation material will degrade, leading to increased losses in the energy conversion process. For a 250 kW motor, if the temperature exceeds 75°C, the motor efficiency may drop by 2%-3%.

After installing an intelligent control system, a motor can automatically adjust its voltage and frequency based on the load, improving energy conversion efficiency by approximately 5%-10%. For example, a 3 MW wind turbine can achieve an energy conversion efficiency of 45%-50% at a wind speed of 12 m/s. With ongoing advancements in wind power technology, future wind turbines may achieve energy conversion efficiencies exceeding 60%.

Slip

Slip is an important indicator of motor efficiency and performance, usually expressed as a percentage. The formula for slip is:

Slip = (Synchronous Speed – Rotor Speed) / Synchronous Speed × 100%

For example, if the synchronous speed is 3000 rpm and the rotor speed is 2950 rpm:

Slip = (3000 – 2950) / 3000 × 100% = 1.67%

Slip typically ranges from 0.5% to 6%. For a 150 kW motor with a 3% slip, the rotor speed would be 2910 rpm, which is 3% lower than the synchronous speed. Under light load, the slip may be as low as 0.5% to 1%, resulting in lower energy losses and higher efficiency.

In large industrial applications, a 500 kW motor may have a slip of only 1% under light load, but under full load, the slip can increase to 4%-5%. A 250 kW motor made with high-conductivity materials for the rotor can reduce the slip by 0.5%, which increases the motor’s efficiency by 2%-3%. Slip is typically controlled between 1%-2%.

For a 1,000 kW motor using a variable frequency drive, the slip remains around 1% under low load, but increases to 3%-4% under high load. For a 400 kW motor, if the slip is high, the power factor may drop from 0.95 to 0.9, reducing the effective output power by 5%.

For a high-efficiency motor with a current of 250 amps, when the load increases and the slip increases, the current may rise to 300 amps. A 600 kW motor running at full load with a slip of 5% will cause additional heat in the rotor, increasing the motor’s temperature by 5°C to 10°C.

Torque Generation

For a 100 kW motor, the stator generates a rotating magnetic field with a frequency of 50 Hz, giving a synchronous speed of 3000 rpm. For a 150 kW motor, when the rotor speed is 2950 rpm, and the stator’s synchronous speed is 3000 rpm, the slip is 1.67%.

For a 200 kW motor, the rated current is about 300 amps. When the motor’s load increases by 50%, the current can rise to 450 amps. Based on the electromagnetic relationship between the stator and rotor, the maximum torque that the motor can generate is usually about 1.5 times its rated torque.

A 250 kW motor, with improved design reducing electromagnetic losses by 15%, can increase torque generation efficiency by 5%-7%, which results in a 10%-12% reduction in energy consumption for the same power output. A 1,000 kW motor running under no load generates 10%-20% of its rated torque.

At startup, the motor’s torque is typically 5 to 7 times the rated torque. This high starting torque leads to a very high starting current, usually 6 to 8 times the rated current.